The 8-1 decision in Rahimi upholding Zachey Rahimi’s conviction for possessing a firearm while subject to a domestic violence restraining order is a fairly narrow opinion in many ways. As Justice Neil Gorsuch noted in his concurring opinion (we’ll have more to come on that opinion and the other concurrence), the ruling does not address lifetime bans on gun possession for those convicted of felonies or misdemeanors punishable by more than a year in prison, “whether the government may disarm a person without a judicial finding that he poses a ‘credible threat’ to another’s physical safety,” or the constitutionality of “other laws denying firearms on a categorical basis to any group of persons a legislature happens to deem, as the government puts it, ‘not ‘responsible.’”

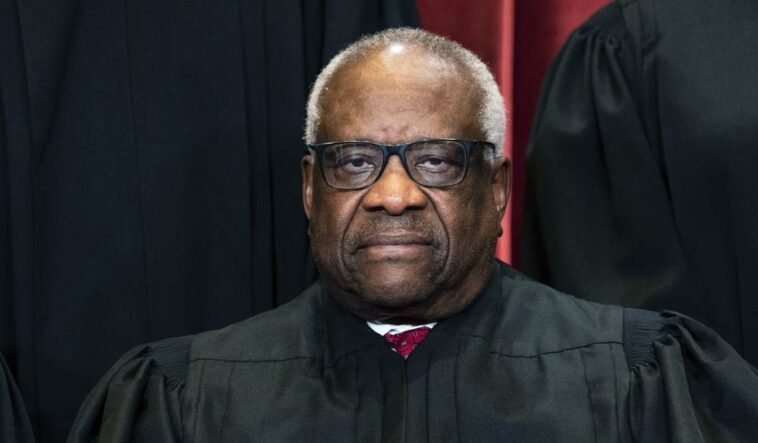

But the lone dissenter in Rahimi still believes that the decision still opens the door for those types of bans to be upheld. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for a minority of one, held that the government failed to show any historical statute or tradition that was materially similar to the modern prohibition on gun possession for those subject to a domestic violence restraining order. While Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, cited surety laws and statutes against “affray”, Thomas says those laws are substantially different from Section 922(g)(8) and don’t pass the “history, text, and tradition” test spelled out in Bruen.

The Court recognizes that surety and affray laws on their own are not enough. So it takes pieces from each to stitch together an analogue for §922(g)(8). Our precedents foreclose that approach. The question before us is whether a single historical law has both a comparable burden and justification as §922(g)(8), not whether several laws can be cobbled together to qualify. As Bruen explained, “determining whether a historical regulation is a proper analogue for a distinctly modern firearm regulation requires a determination of whether the two regulations”— the historical and modern regulations—“are ‘relevantly similar.’” In doing so, a court must consider whether that single historical regulation “impose[s] a comparable burden on the right of armed self defense and whether that burden is comparably justified.”

Surety laws didn’t prohibit those subject to them from possessing or (in many cases) bearing arms. Instead, it required them to post a bond before they could do so. And affray laws, as Thomas pointed out, “were criminal statutes that penalized past behavior, whereas §922(g)(8) is triggered by a civil restraining order that seeks to prevent future behavior.”

Thomas went on to say that the “mixing and matching” of historical laws that rely on one law’s burden and another law’s justification “defeats the purpose of a historical inquiry altogether.”

Given that imprisonment (which involved disarmament) existed at the founding, the Government can always satisfy this newly minted comparable-burden requirement. That means the Government need only find a historical law with a comparable justification to validate modern disarmament regimes. As a result, historical laws fining certain behavior could justify completely disarming a person for the same behavior. That is the exact sort of “regulatory blank check” that Bruen warns against and the American people ratified the Second Amendment to preclude.

Second Amendment attorney Kostas Moros also sees danger in the analogues accepted by the Court, which he says is likely to lead to lower courts upholding gun control laws based on even more dissimilar statutes from history.

Thomas did acknowledge and agree with the majority’s rejection of the DOJ’s contention that the Second Amendment can only be exercised by “responsible” citizens, but warned that today’s decision will weaken the history, text, and tradition test.

The Court rightly rejects the Government’s approach by concluding that any modern regulation must be justified by specific historical regulations. But, the Court should remain wary of any theory in the future that would exchange the Second Amendment’s boundary line— “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed”—for vague (and dubious) principles with contours defined by whoever happens to be in power.

… The Framers and ratifying public understood “that the right to keep and bear arms was essential to the preservation of liberty.” McDonald, 561 U. S., at 858 (THOMAS, J.,concurring in part and concurring in judgment). Yet, in the interest of ensuring the Government can regulate one subset of society, today’s decision puts at risk the Second Amendment rights of many more.

I suspect Thomas is right. While there are portions of Rahimi and several of the concurrence that may prove helpful to Second Amendment advocates going forward (which will be the topic of another post this afternoon), today’s decision will do nothing to put the brakes on lower courts upholding gun control laws using the most specious arguments. If anything, the majority opinion in Rahimi is likely going to lead lower court judges to rev up their activism. Gorsuch is arguing that today’s decision leaves many questions unanswered, but Thomas contends that even if that is the case, Rahimi is going to make it much easier to rule against gun owners in the future.